Renovating vs Building New: What's Best for Public Architecture?

Renovating vs Building New – A Framework for Public Architecture

Across Michigan and beyond, city officials, school administrators, and community leaders face a familiar challenge: what to do with aging public buildings.

When maintenance costs rise, accessibility falls short, and spaces no longer meet community needs, the question arises: Is it better to renovate or build new?

This decision is never simple. It balances cost, community values, and long-term impact.

At Partners in Architecture, we help guide municipalities and school districts through this process with honesty, transparency, and a focus on designing for the greater good.

When it comes to municipal architecture, one of the most important questions communities face is whether to renovate or build new.

In this blog post, we’ll break down the key factors that guide the choice to renovate or build new, share examples from public projects, and clear up common misconceptions.

4 Factors That Drive the Decision to Renovate or Build New

When municipal leaders are faced with an aging facility, one of the first steps is weighing the pros and cons of renovation versus new construction.

The decision is rarely black and white. It involves careful consideration of cost, condition, and the role the building plays in the community.

1. Cost Considerations

Budget is always at the center of the discussion. Renovating an existing structure may appear less expensive at first, but a deeper look often reveals hidden costs. An old home or school building, for example, may require remediation for asbestos, outdated wiring, or mechanical systems that no longer meet modern standards. On the other hand, building a new structure typically requires higher upfront investment but often results in lower long-term operating costs and greater efficiency.

2. Condition of the Building

The age and condition of the facility play a major role. Just as with old houses, the question isn’t simply whether the walls still stand. We ask whether the infrastructure can support today’s technology, safety requirements, and accessibility standards. Sometimes the shell of the building is sound and well-maintained, making a renovation project viable. Other times, years of deferred maintenance make renovation a costly uphill climb.

3. Functionality and Adaptability

Public architecture must be flexible enough to support both current and future needs. A remodel may create more functional living space for a library, school, or civic building, but only if the existing layout allows for it. In contrast, building a new municipal facility offers the opportunity to design spaces that are tailored to today’s users and adaptable for decades to come. For school districts, safety and security are central to the decision-making process, which is why we also explore

designing safer schools as part of our work.

4. Community Value

Numbers tell only part of the story. Civic buildings often carry deep cultural and historical meaning for residents. Preserving a landmark school can reinforce civic pride, while constructing a new, modern building can symbolize progress and future growth. For example, Roseville Community Schools determined that consolidating three outdated elementaries into one efficient, centrally located new building best served their students and community—a decision that balanced both financial responsibility and community needs.

In the end, the choice between renovation and new construction requires balancing the tangible costs with the intangible values of history, identity, and community purpose.

Facility Assessments: A Roadmap for Municipal Architecture

Because every public building has its own story, no two decisions about renovation or new construction are alike. That’s why a facility assessment is such a critical step in the process.

At Partners in Architecture, we use a structured, transparent framework to help communities see the full picture before making a decision.

Our assessments break needs into three categories:

- Priority One – Critical issues that must be addressed within 1–3 years, such as life-safety concerns, accessibility requirements, or failing infrastructure.

- Priority Two – Needs within 3–5 years, which may include building systems nearing the end of their service life or spaces that limit day-to-day functionality.

- Priority Three – Long-term improvements planned over 5–10 years, often tied to efficiency upgrades, modernization, or program expansion.

This approach gives leaders a roadmap that highlights immediate risks while also charting a sustainable path forward. It allows them to weigh the cost of addressing current problems against the investment of starting fresh. Just as importantly, it ensures decisions are based on facts rather than assumptions.

Assessments also help ensure buildings can adapt to changing community needs, whether that’s a school, library, or an emergency operations center.

For example, at Macomb County Jail, initial conversations leaned toward tearing down the existing building and constructing an entirely new facility.

But the assessment showed that a hybrid solution would be more practical: demolishing the most outdated sections, adding new construction where it was needed, and renovating portions that were still sound. This blend of strategies not only saved costs but also minimized disruption to ongoing operations.

Facility assessments don’t provide the answer; they provide the clarity leaders need to make the right choice for their community.

By outlining the condition of the building, estimating costs over time, and organizing priorities, assessments become a powerful tool for municipalities to plan responsibly for the future.

Why Listening Matters: Stakeholders and Community Voices

Decisions about civic buildings shape the daily lives of the people who use and value them. That’s why listening is central to the process.

Stakeholders include administrators balancing resources, finance teams structuring funding, and end-users like teachers, staff, or public service employees who know what works (and doesn’t) in their spaces.

The broader community also plays a critical role, especially when bond elections or tax support are involved.

A powerful example comes from Mount Clemens, MI, where a historic high school faced possible demolition.

While the cost analysis leaned toward replacement, alumni and residents voiced strong opposition. Their input ultimately preserved the building, underscoring how public architecture decisions must honor both financial realities and community identity.

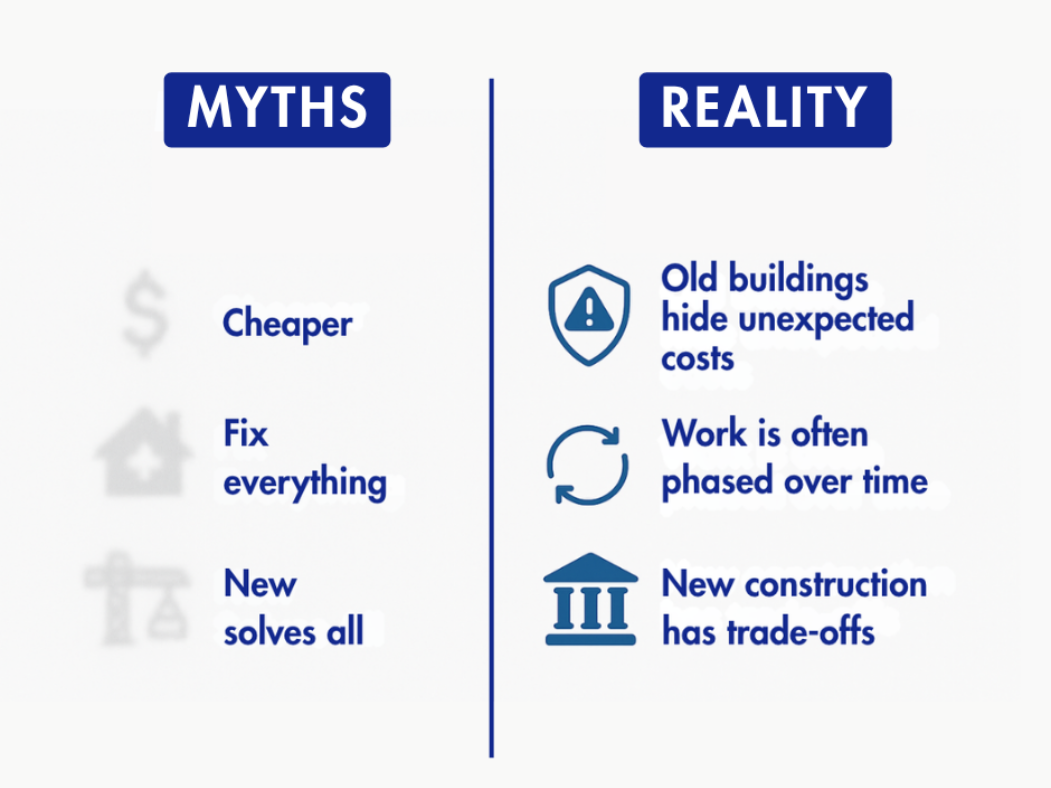

Dispelling Myths About Renovation vs New Construction

When communities weigh whether to renovate or build new, certain misconceptions often shape the conversation. These assumptions can complicate decision-making and sometimes lead to unrealistic expectations.

At Partners in Architecture, part of our role is to bring clarity and help leaders understand what’s truly at stake.

- Myth #1: Renovation is always cheaper. While it can be less costly in some cases, older buildings often hide challenges, hazardous materials, outdated infrastructure, or layouts that don’t support modern technology. These issues add expense and can narrow the gap between the cost of renovating and building new.

- Myth #2: A renovation project should fix everything at once. In reality, most communities phase their work over time. Critical safety or accessibility upgrades might come first, with other improvements planned years later as funding becomes available. This phased approach makes projects more affordable, even though it sometimes leaves parts of a facility untouched in the short term.

- Myth #3: A new building solves every problem. New construction offers a blank slate, but it also comes with trade-offs. Demolition can erase a piece of community history, and higher upfront costs may strain available funding. A new facility isn’t automatically better if it doesn’t align with long-term goals or community values.

By addressing these myths directly, we help clients approach the decision with clear eyes. Whether the solution is renovation, new construction, or a combination of the two, what matters most is that the investment supports the people who use the building every day.

Renovate or Build New? Designing Public Buildings with Purpose

The choice between renovating and building new is rarely simple. It requires comparing dollar amounts, and understanding a building’s condition, weighing community values, and planning for the future.

A thoughtful decision can extend the life of a facility and preserve history, or it can create a modern, efficient space designed to serve generations to come.

At Partners in Architecture, we believe every civic building, whether renewed through renovation or created from the ground up, is an opportunity to strengthen the community it serves.

Our role is to listen first, provide clear analysis, and guide leaders toward solutions that balance cost, functionality, and long-term value.

If your community is facing this decision, we’d be honored to help.

Contact Partners in Architecture to schedule a consultation

about how we can support your next project—together, we can design with purpose for the greater good.

Frequently Asked Questions:

Is renovating always less expensive than building new?

Not always. Renovation may look less costly upfront, but older buildings often come with hidden expenses such as hazardous materials or outdated systems. A new facility can sometimes be more cost-effective over its full lifecycle.

How does a facility assessment help with the decision?

A facility assessment gives leaders a clear picture of current building conditions and future needs. By prioritizing issues and estimating costs over time, it allows communities to compare renovation and new construction side by side.

Can we do both—renovate part of a building and add new construction?

Yes. In many cases, a hybrid approach is the most practical. For example, removing outdated sections, building an addition, and renovating what still works can balance costs while meeting modern needs.

What role does the community play in these decisions?

Community input is essential, especially for civic buildings with historical or cultural value. In some cases, strong community voices have preserved older buildings that might otherwise have been replaced

How do we know which option is right for our situation?

Every project is unique. The best path forward depends on the condition of the existing structure, available funding, and the needs of the people who will use the building. Working with an experienced partner like PIA ensures you have the data and guidance to make an informed decision.